China’s Drought: It’s Our Problem Too

February 15, 2011 § 4 Comments

China’s drought is bad, the worst in at least 60 years. Roughly 12.5 million acres of winter wheat crop have been damaged. And a United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) alert reported last week that 2.57 million people and 2.79 million livestock are suffering from shortage of drinking water.

The mood in China is not upbeat, as forecasters are predicting that the drought may well continue into the late spring-early summer months–threatening the summer wheat crop. And though the Chinese might have a reasonable amount of wheat stockpiled, no analyst I’ve read pretends to know with certainty how deep the stock goes or how long, in the face of unyielding drought, it can sustain the needs of the population. What we do know is that the prospect of a China running low on water and wheat is not pretty–for anyone.

China is the largest wheat-producing (and wheat-consuming) country in the world. Wheat shortage there means not only that prices in China will rise, but also that prices on the international market will go up.

Some pundits have already argued that the recent unrest in Tunisia and Egypt was prompted in part by surging food costs. Global wheat prices jumped 77% in 2010 (a spike that continues unabated into 2011). If China is forced to turn to the international wheat market, how steep will global prices rise? Will China’s demand resulting shortages elsewhere? And will shortages and steeper prices, in turn, lead to social and political unrest in other spots of the world?

Other pundits remind us that if the current Chinese wheat harvest is a bust, China will likely look to the U.S. market for imports. How will Chinese import demand affect wheat supply and prices here? And will this demand contribute to growing inflation in the U.S.?

Inflationary pressures in China are already high. The present drought only exacerbates these pressures. The anxiety of the Beijing government is palpable. President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao have made personal visits to the stricken areas calling for “all-out efforts to combat drought” and committing $1billion to fight the devastation. They’ve made television appearances assuring the people that the government has abundant stockpiled wheat and is taking all possible measures to maintain the balance between supply and demand of the grain. What Hu and Wen, of course, know is that droughts and famines have made for restive populations in China’s past–they’ve even toppled governments (the Taiping and Boxer rebellions of the 19th and earlier 20th century are still fresh in their minds and Huang Chao’s rebellion at the end of the Tang dynasty (618-907) has a place in their high school history texts).

So, the Beijing government continues to fire the cloud-seeding chemical silver iodide into the atmosphere to encourage more snowfall (to little effect, however, according to reports in the China Daily and the Global Times).

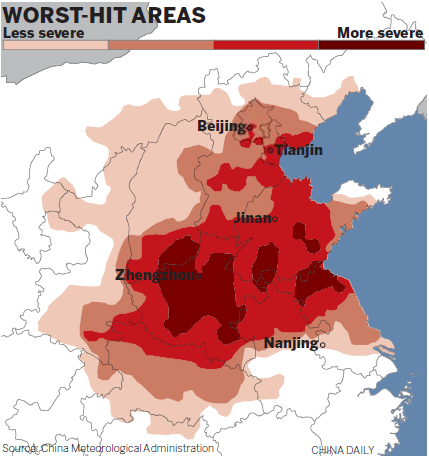

It’s begun digging 1350 emergency wells, constructing irrigation facilities, and planning water-diversion projects in the major wheat-growing provinces affected by the drought.

And it’s handing out $334 million in emergency relief aid to farmers.

Such measures by the Chinese government are intended principally to ease the burden on the Chinese people and to ensure social and political stability. But, given the global repercussions of a severe wheat shortage in China (or, indeed, anywhere in the world, as events in Tunisia and Egypt have suggested), Beijing’s aggressive efforts to deal with the crisis should be welcome by all.

Confucius: It’s His Birthday and He’s Back, Sort Of

October 1, 2010 § 2 Comments

This post reproduces an op-ed piece from today’s LA Times (October 1) on the so-called revival of Confucianism in China today–especially in government circles.

What Confucius says is useful to China’s rulers

The venerable sage’s teachings have enjoyed a revival in 21st century China because they serve the communist regime well politically.

Confucius, the venerable sage who lived in the 6th century BC, is enjoying a 21st century revival. His rehabilitators? The Chinese Communist Party. Yes, that party, the one celebrating the 61st anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1. The same party whose chairman, Mao Tse-tung, vilified Confucius’ “stinking corpse” during the Cultural Revolution and ordered the Red Guards to destroy all temples, statues, historical landmarks and texts associated with the sage. But, as China turns 61, the Great Helmsman is out and Confucius, who would have turned 2,561 on Sept. 28, is in.

As early as February 2005, the Beijing leadership began endorsing the sage’s teachings again, citing him approvingly in a speech delivered to the National Congress by President Hu Jintao: “Confucius said, ‘Harmony is something to be cherished.’ ” Since then the terms “harmonious society” and “harmonious world” have become mantras of the party leaders and the basis of their domestic and foreign policies. During the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Olympics, the world was greeted not by quotations from Mao’s Little Red Book but by warm homilies from the teachings of Confucius.

What explains this redemption? Confucius gave attention to two overarching matters: what makes for good government, and what makes for a morally good individual. His answers were elegant — and compelling — in their simplicity. Good government rules not by physical force but through moral force. The ideal ruler embodies virtue, which is expressed in his unfailingly benevolent treatment of the people. In turn, the people voluntarily, even eagerly, choose to follow him.

Because government, to be good, requires a good ruler — and good officials — Confucius also characterizes what makes for a good person: someone who possesses a love of learning; strives to achieve benevolence, righteousness, propriety and wisdom; treats others as he would wish to be treated; is trustworthy and loyal as a friend, filial as a son and obedient as a subject; and, reciprocally, is affectionate and caring as a parent or an official.

What in this millenniums-old vision resonates with Beijing today?

With the proclamation “to get rich is glorious,” Deng Xiaoping, China’s paramount leader for two decades beginning in the late 1970s, ushered in the post-Mao era. An ideology of socialist revolution through class warfare gave way to an ideology of getting rich. And, of course, the Chinese — or at least some — have since become very wealthy indeed. But unbridled economic growth has spawned a host of problems: a widening gulf between rich and poor, urban and rural; heightened social tensions; increasing unemployment; rising crime; rampant corruption, especially among government officials and local business leaders; environmental degradation; healthcare and elderly care that is out of the reach of vast numbers of people; and a skyrocketing incidence of public protests (tens of thousands annually).

The Communist Party is neither unaware of nor insensitive to these problems. But it is determined to confront them without surrendering any of its political control or authority; it has shown little inclination to make substantive changes to the prevailing political system or institutions of government.

In the ideology of Confucianism, party leadership has rediscovered a potent language for addressing the challenges China now faces. The teachings of the sage, after all, offer the promise of social harmony. The crux of the Confucian agenda is that individuals, whatever their social or economic status, are to treat their fellow human beings empathetically and with proper respect. A philanthropic, communal spirit imbues humanity, creating a society in which “all within the four seas are brothers.” Here the Beijing leadership sees an opportunity to lessen the wealth gap and ease social tensions — and at little financial cost to the government.

And if official corruption is one of the most serious grievances among the people — frequently capable of sparking social unrest — traditional Confucian teachings again provide authorities with the language to show the people that they are attacking it head-on. The official China Daily observed in 2007: “In traditional Confucianism, the cultivation of personal moral integrity is considered the most basic quality for an honest official. The qualities of uprightness, modesty, hard work, frugality and honesty that President Hu encourages officials to incorporate into their work and lifestyle are exactly the same as the moral integrity of a decent person in traditional culture.”

Confucius promises a government that cares for the people, that makes their well-being its primary concern. This is to govern by virtue. And virtue creates its own legitimacy: paternalistic, affectionate care of the people by the rulers is sure to be reciprocated by the people’s trust and obedience. Hu Jintao’s appropriation of the language of Confucianism not only fills the ideological void left by Marxist-Leninism’s demise but also suggests to the governed that, in seeking to create a harmonious society and a harmonious world, he and other officials take their “Confucian” responsibility of moral leadership to heart. Their expectation is that the people, in turn, will place trust in the government and be obedient to it, with minimal dissent.

China’s government appears determined to address the fissures and tensions born of almost three decades of unrestrained economic development. But it seems equally determined to bring about such change without reforming the prevailing one-party system of governance. The regime in Beijing, eager to keep its power intact, to maintain the political status quo, has chosen, for the time being, to goad the Chinese toward social harmony through traditional ideological and moral exhortations.

Resuscitating the sage today thus serves the party’s political aims. But to conclude that cherry-picking soothing phrases from Confucian writings is the same as a genuine and enduring commitment to the vision of Confucius would be a mistake.

Daniel K. Gardner is a professor of history and the director of the program in East Asian studies at Smith College.

Copyright © 2010, Los Angeles Times